What About the Little Guys? “Banned” Books from the Authors’ Perspective

Book censorship is certainly not a new thing to grace the desks of Legislature. In fact, it's been in the United States for hundreds of years; the first known ban was in Quincy, Massachusetts in 1637. The purpose of book banning has generally been touted to “protect” readers. Books that promote ideas that do not fit a certain political narrative are viewed as incendiary or obscene, or are otherwise deemed “unfit” for public consumption, and are censored or banned by authorities. Modern-day censorship is primarily focused on “protecting” children.

Many think that for an author, getting their book banned is a badge of honor. That their sales will skyrocket with the free publicity. But this is only true for “celebrity” authors, or authors who are already a household name. What about the little guys? Those indie authors or first-time authors who have yet to form a large readership. How does book banning affect them? Is there a way to write a book so that it isn't banned? In September 2022, the Texas Tribune shared a list of over 800 books that former Texas House Representative, Matt Krause, challenged to ban or banned from schools and public libraries up to October 2021. We used this list to contact lesser-known authors who shared their perspectives.

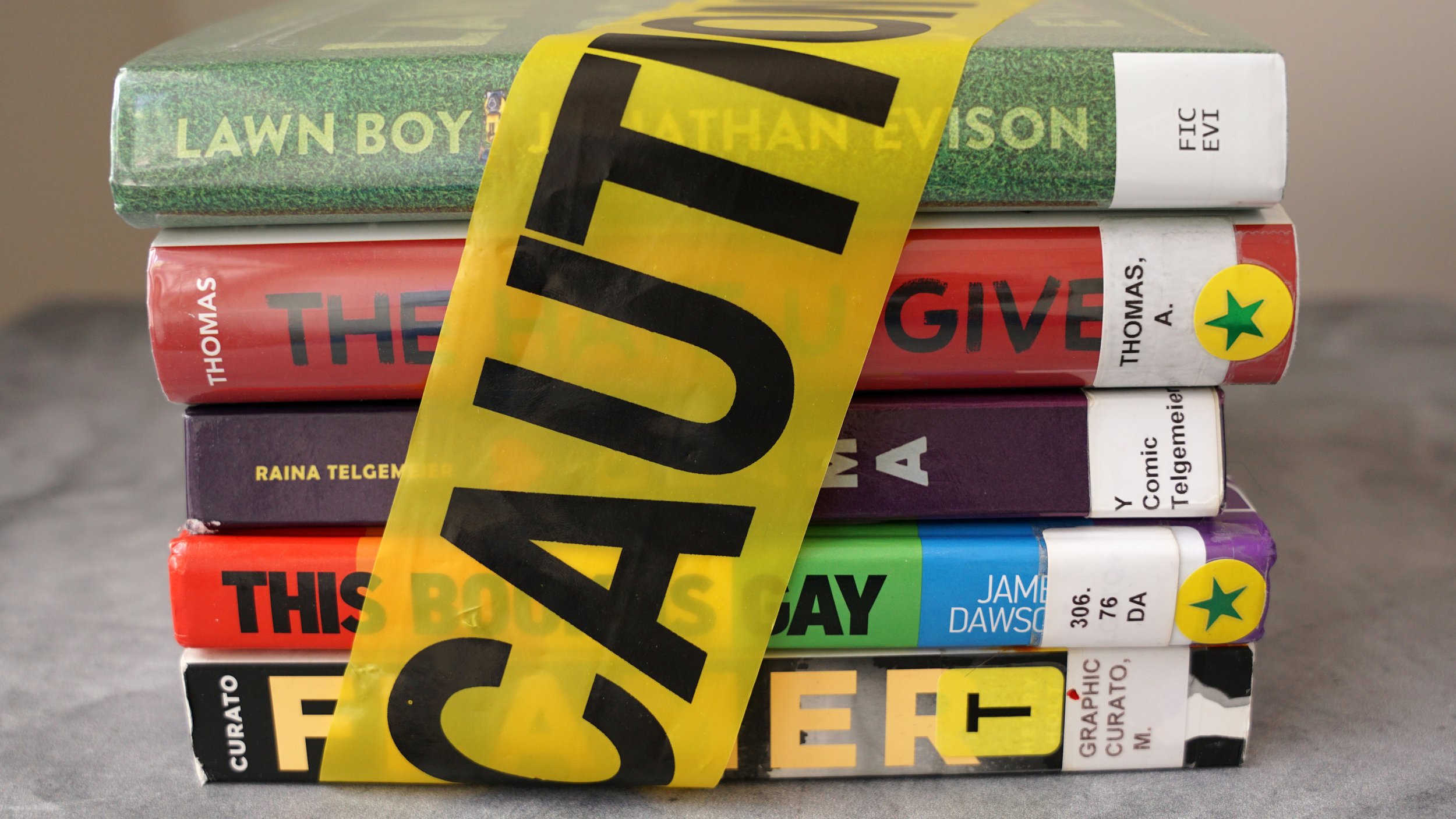

Many bookstores and libraries have an affinity for banned book display tables, often redundant with the routine handful of famous banned classics: George Orwell’s 1984, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, or Margeret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Display tables are meant to uncensor the censored, but instead, they exacerbate the problem. First time or lesser-known authors suffer in the background, and so do the communities they represent.

“We see tables at Barnes and Noble with the same twenty titles of banned books we already know,” stated Lexie Bean, author of The Ship We Built. “These banned lists have thousands of titles, mainly by first-time authors and authors writing from marginalized communities. This has a real impact on our careers, sense of self, and ability to make our work accessible.” It affects their new projects as well. “I can be met with a lot of fear,” Bean said. “It means that future books that I pitch are less likely to be given the green light.” For example, they described how their editor warned them that the sexual abuse content in their book would be seen as controversial. When Bean insisted on including it, their editor asked them to write an author’s note to provide context. After the book came out, “a lot of the attention that [the publisher] got or a lot of the collaboration that happened was actually because of the survivor narrative. Organizations like RAINN: The Rape, Assault, Incest, Natural Network [have it on their] recommended list.”

Steven Salvatore, talking about his books And They Lived . . . and Can’t Take It Away, said, “I'm not seeing an increase in sales because my books are being banned. In fact, I think that it's just hurting whatever sales numbers I have because it means less libraries, less school districts are buying my book. If they're not buying my book and there's less exposure, then it's just less of a chance for other readers to get my book as well.” Salvatore added, “It's not just LGBTQ characters and authors that are subjected to censorship. Any book that features any sort of minority character is going to be challenged. I think publishers know that, and a lot of that goes into how they position and market a book.”

Removing books from libraries or schools mutes the voices of the unrepresented and makes individuals who are part of those groups feel invisible or alone, unaware there are others who feel like them. Several of our authors identified with these sentiments.

Romina Garber (Lobizona) responded, “I wrote the book I wished I’d had as a teen—about an Argentine immigrant who stumbles into her magical heritage & grapples with what it means to come from two worlds but belong to neither. Often, that is how I have felt about being an immigrant—no longer Argentine enough for Argentina, & a secondhand citizen in the US. As a naturalized immigrant, I can never be President, so by definition I’m ‘less than’ a natural-born citizen. I hoped to create a home where teens like me would feel welcome.”

Similarly, Cassandra Rose Clarke says she wrote Forget This Ever Happened because she wanted to write the kind of book she would’ve loved in middle school. “I wanted it to have the kind of LGBTQ+ representation that would have helped me better understand my own sexuality—I’m bisexual—when I was that age. My primary goal was to write something fun and weird and a little scary—think Fear Street but sci-fi.”

“I wrote A Good Kind of Trouble because I wanted to write a book that was similar to books I read and loved growing up but that but that featured a Black protagonist,” responded Lisa Moore Ramee. “All the books that I read as a kid were with white characters. I didn't even notice until I read my first book with a main Black character—The Skin I'm In. My daughter was the age of the main character when I started working on the book, and the lack of books available that featured characters that looked like her was troubling. I also had several white friends who were curious and had questions about Black Lives Matter, and I knew explaining that movement from a young person's perspective would make it much easier to understand.”

When authorities ban lesser-known authors’ books, they are silencing those marginalized voices, and audiences that feel represented in those books can no longer see they are not alone in their identity. “When you remove books like mine from the shelves of libraries, you are basically erasing those kids,” wrote Greg Howard, author of Middle School’s a Drag, You Better Werk!, which deals with LGBTQ+ themes. “You are telling them that their story doesn’t matter and that they don’t have any value in our society.” The question remains, who is truly being harmed by these bans? Garber stated “It’s saying to us that our stories—our identities—do not deserve to be shared or celebrated. It’s just confirming what we have long suspected: We are powerful, and that terrifies the people in power.”

Ginny Rorby agrees: “I originally wrote Freeing Finch as an abandoned dog story. It was resting comfortably in a bottom drawer until a seventy-year-old orthopedic surgeon friend of mine came out as trans and had confirmation surgery. Once over the initial shock, I wanted to know about transgenderism. Dr. Rohr was very open to sharing her story and helping with the research. Her surgery was featured in the Washington Post, and she and her wife of more than forty years were featured in the National Geographic/Katie Couric documentary on transgenderism. Freeing Finch became my attempt to share what I learned with the more open and responsive minds of the young.”

In addition to responding to our survey, Lexie Bean sat down with us via Zoom to discuss their publishing career. “I've learned that writing the most honestly sometimes involves thinking about an audience of one. What ultimately encouraged me was knowing there were no middle grade books focused on trans boys openly written by one at the time. With that, I felt immense responsibility to offer something nuanced and alive.”

Shay Mirk is one author who wanted to open discussion on a potentially controversial topic. Her book, You Do You: Figuring out Your Body, Dating, and Sexuality (written as Sarah Mirk), discusses teen sexuality. “I think discussion of healthy dating dynamics and sexual health is extremely important for teens. Everyone deserves to know everything possible about how their bodies work, and I wanted to create a queer-inclusive book that felt empowering and supportive for teens,” Mirk said “I hope that this book can be useful to teens in building healthy friendships and romantic relationships, as well as positive relationships with their own bodies. The big message of the book is ‘there is no normal.' Every body is different. A lot of shame and isolation teens experience comes from feeling like they're weird or the only person experiencing something. I hope this book helps teens feel like whatever is happening with their body and their sexuality, they're not alone.”

However, most authors who responded to our survey were not attempting to start discussions about controversial topics. They just wanted to tell their stories, describe their realities, and live their truths. And if the subject is viewed as controversial, then so be it. Sometimes, reality can be contentious and often inconvenient to others. The purpose is to put their reflection of life on the page, and this is wonderfully illustrated by several authors.

For example, Adib Khorram, the author of Darius the Great Deserves Better, stated, “I reject the premise [that most contemporary banned books were written to open discussion on controversial topics] as I do not believe the existence of BIPOC, queer people, disabled people, or otherwise marginalized people—which is often the sole complaint in a challenge or ban of a book—is controversial, and to suggest that our lives are somehow controversial is dehumanizing.”

Howard stated it in this manner: “I don’t know any writer who sets out to write about controversial topics just for the sake of writing about controversial topics. We are driven by story and characters, not discussion topics. And keep in mind, some of our stories are deemed ‘controversial’ by adults coming from a place of fear of what they don’t understand and nothing more.”

Ryan La Sala, the author of Be Dazzled, reflected on his perspective on why his book was banned. “I don't think I can really speak for most contemporary banned books—the list is so long, and I'm sure the goals are very diverse amongst the authors that set out to write their books. I also wouldn't agree that most contemporary banned books present controversial topics. Speaking personally, I don't think the queer characters in my books are actually controversial. I think my books have been banned in the hopes of generating controversy around queerness, but this is a response to the queer culture already being mainstream for a book like mine to be published.”

G.S. Prendergast, author of Cold Falling White, lent her voice to the discussion in this manner: “I can't speak for other authors, but I try to create fictional worlds that young readers can recognize and relate to. Most books that appear on banned lists are simply depicting normal parts of life, even ones set in a science fiction or fantasy world. But I think it is telling how skewed banned lists are towards realistic fiction. It's almost as though the objectors to these books object to reality itself.”

Garber asserted, “Creating literature and generating discussion are not mutually exclusive—rather, they go hand in hand. Think of Jane Eyre, which is a Gothic novel as much as it is a feminist social critique of its time. Pride & Prejudice is a romance as much as it is a critique of the class structure and gender inequality of early nineteenth-century England. One Hundred Years of Solitude is a fantasy that uses magical realism to allegorize the Latin American identity & explore predominant issues like machismo, rebellion, and political violence. I find that the best literature does more than entertain: It teaches us about the world around us and the worlds within us.”

Ramee gave a more animated explanation. passionately expounding, “Being Black is not controversial. Describing life from the perspective of someone who is, is not controversial. I also am not concerned with the idea of creating literature. I have a Master's in English Literature. I'm not creating a body of work for folks to study; I am creating a body of work for (primarily) young people to enjoy. Simply put, I want to tell a good story.”

Almost unanimously, the authors believed that their books could not be rewritten to avoid banning while staying true to their original intent. Possibly because it is not the books themselves that are banned; it is someone’s idea or a particular agenda that deems the subject matter presented in the books forbidden or taboo. Often, this needle tends to move that banned books would be erroneous even if the “controversial” subject matter is omitted or changed for universal acceptance. “The reasons given for banning specific books are only excuses,” Nikki Smith, the author of The Deep Dark Blue, articulated. “Books are rarely fully read before being challenged; specific words or lines are quoted without consideration for context or story. Book banners are not interested in nuanced discussions about the books in question. They want to believe that children exist in a bubble, somehow outside of society and ignorant of all its complexities.”

Similarly, Clarke declared, “Most banned books are challenged by a small but vocal minority who are frightened by what the book represents more than what’s actually in it. I seriously doubt that whoever called for Forget This Ever Happened to be banned actually read it. Instead, they saw that it featured a same-sex relationship, which, in their minds, meant the book was ‘inappropriate’ for young readers even though there’s nothing explicit whatsoever in the story. If I were to rewrite Forget This Ever Happened to appease those calling for it to be banned, I would have to make it a straight romance. While the genre elements would remain the same, the book would lose a large part of what makes it special. The story isn’t ‘about’ being gay or bi, but cutting those elements would change it for the worse—because if I had seen a bisexual character like the one in the book when I was twelve or thirteen, it would have been life-changing.”

Bean answered, “I believe there is not another way I could have told this story. I can't speak for most authors or books, but I can share about my own. My original intention was to be honest and write from a place of love. This ultimately meant being truthful about the protagonists' journey with gender, experiences of abuse, regionalism, and more. He writes letters and attaches them to balloons with the hopes of there being someone out there who can understand. He speaks quietly, and with language a ten-year-old uses to understand what does not yet have words. On some days, he even protects the reader from his truths because he is scared, unsure, or alone. It is not a comfortable life; it is not a comfortable text. That doesn't mean it's not meant for young readers.”

Mirk declared, “I don't think it's possible to write a useful and relevant book that no one will take offense to. You Do You, for example, is extremely positive. The message is one that I would think everyone can get behind: we can celebrate the diversity of humanity while helping teens know what's going on with their bodies. That seems pretty basic and inoffensive! If you take away that intent, there is no book.”

The author of Blood Sport, Tash McAdams, highlights the absurdity. “The very fact that we are discussing how to make a book dance around some invisible, impossible-to-meet standards is ridiculous. Bigots don’t just want to keep us out of books, they want to keep us out of the world and don’t care that it kills us.”

The real question is, which children are harmed by these books and the efforts to censor them: the ones being “protected” or the ones who identify with the characters in these books? As Smith put it, “When diverse voices are silenced and oppressed, we all suffer.”